Teams often assume that a patent search and a Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis are interchangeable. In reality, they answer two completely different questions, serve different stages of product development, and carry dramatically different legal consequences. I’ve seen startups proudly say “We checked patentability, so we’re safe to launch,” only to realise months later that patentability has nothing to do with infringement risk. This confusion is widespread—even within engineering and IP teams of well-funded companies—and the consequences can be expensive. Understanding the distinction is fundamental to scaling a product safely in India, the US and the EU.

What Is the Difference Between an FTO Search and a Patentability Search?

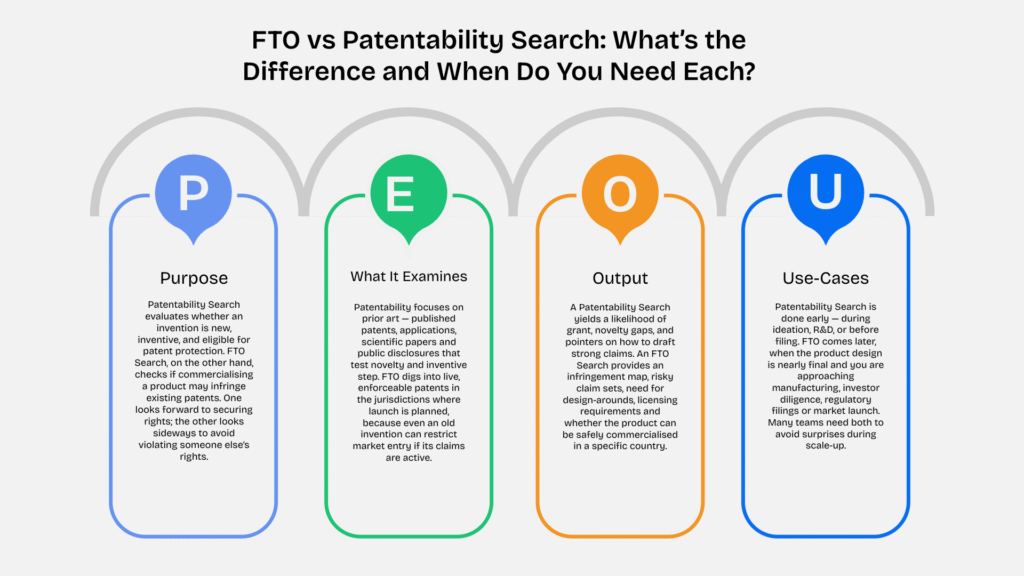

A patentability search asks whether your invention is new and patentable. A Freedom to Operate (FTO) search asks whether your product infringes someone else’s active patent. Patentability lets you file your own patent; FTO determines whether you can legally sell the product in a specific country.

Patentability Search: What It Actually Covers

A patentability search is an innovation-focused assessment. It examines prior art to determine whether your invention is novel, involves inventive step, and is industrially applicable. It does not look at enforceable patents or active claim coverage in specific jurisdictions. Instead, it looks broadly at older publications, expired patents, research papers, conference proceedings, public disclosures and technical literature. The purpose is to figure out whether you can obtain a patent—not whether your product infringes one.

This is why patentability searches often include expired patents. They help understand the state of the art but have zero relevance to infringement risk. Patentability is strategic: it helps build IP value, create defensible differentiation, and position your company for investors. But it does not protect you during product launch.

FTO Search: A Legal and Commercial Risk Assessment

An FTO search, in contrast, is a legally oriented analysis. It focuses only on live, enforceable patents and their active claims in specific jurisdictions. A strong FTO determines whether selling, using, importing or manufacturing a product may infringe an existing patent. It requires careful claim interpretation, legal-status verification, and jurisdiction-specific analysis.

FTO is ultimately about market-entry safety. It’s closely linked to competition, product timing, regulatory submissions and manufacturing decisions. Unlike patentability, which is global and exploratory, FTO is jurisdiction-specific and risk-driven. A product may be patentable globally but infringing in India—or vice versa.

If needed, this is where our earlier article on FTO methodology (How to Conduct a Freedom to Operate Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide (India, US, EU)) becomes a useful reference point for understanding defensibility and claim mapping.

Why the Confusion Exists

Most teams believe that if an invention is new, it cannot infringe anything. But infringement has nothing to do with novelty. You may create a new product that adds an extra feature, improves performance or changes design—yet still incorporates one essential element of someone else’s claim. Indian, US and EU courts look strictly at claim coverage, not originality of the final product.

This is why relying solely on patentability before launch is one of the most common mistakes startups make, especially in med-tech, electronics, AI and deep-tech manufacturing.

When Do You Need a Patentability Search?

A patentability search is most useful at the innovation or R&D stage. When your team is building something new—or feels it is new—this search helps validate whether it makes sense to file a patent. Patentability is also valuable when preparing for investor discussions because it demonstrates potential IP assets.

It also helps identify expired patents that can be used for design inspiration or technical benchmarking. In India, filing early also aligns with start-up friendly incentives such as reduced examination fees and faster processing under the Start-up India scheme. But again, this has nothing to do with clearance for launch.

When Do You Need a Freedom to Operate (FTO) Search?

FTO is required when you are preparing to commercialise a product in a specific country. Whether you are entering India, exporting to the US, or scaling into Europe, an FTO protects you from injunctions, licensing surprises and costly litigation.

A product with a strong patentability report but no FTO can still be blocked from the market. Investors, multinational buyers, OEM partners and regulatory bodies increasingly expect an FTO for hardware, medical devices, IoT systems and AI-driven products. For Indian businesses selling globally, a jurisdiction-specific FTO for India, the US and EU has become a commercial necessity.

For those who need a foundational explanation, our first article on FTO and product launch in India (What Is a Freedom to Operate (FTO) Search and Why Every Product Launch in 2026 Needs One?) remains an excellent entry point.

The Real-World Example Teams Often Miss

Consider a company designing a smart sensor device. The team develops a new integration technique and files a patent. Their patentability search confirms novelty.

But inside the device is a mechanical joint or a communication protocol that someone patented ten years ago—and the patent is still active in India and Europe. The product is original but still infringing. Without an FTO, this risk goes unnoticed until launch, procurement, or a competitor’s legal team surfaces it.

Patentability gives ownership.

FTO gives permission to operate.

Both are needed; one cannot replace the other.

Why You Should Never Substitute One for the Other

Patentability and FTO are strategically aligned but operationally distinct. Filing a patent gives you long-term defensibility, but it does not give you the right to use the invention if someone else holds broader or foundational claims. Similarly, clearing FTO does not guarantee you have protectable IP. The two work together to build both legal protection and market clarity.

In a maturing business ecosystem like India—where investor diligence is sharper and competitors monitor filings closely—treating the two searches as separate but complementary is critical.

FAQs

Is an FTO required even if I have my own patent?

Yes. Your patent gives you exclusivity over your improvement, not immunity from infringing a broader or earlier claim held by another entity.

Can expired patents be used for FTO?

No. Only active and enforceable patents in the target country matter for infringement. Expired patents help only in patentability and design inspiration.

Do I need both searches for every product?

If the product is innovative, yes—patentability builds IP value; FTO ensures safe launch. For non-innovative products, FTO may be sufficient on its own.

Are FTOs jurisdiction-specific?

Always. Patents are territorial. A product free to operate in India may face restrictions in the US or EU.

Wrap Up

Patentability and Freedom to Operate searches serve fundamentally different purposes but are equally important to a product’s lifecycle. One examines novelty; the other examines risk. One builds IP value; the other protects commercialisation. For businesses preparing to scale across India, the US and Europe, understanding and separating these two processes is essential to preventing avoidable litigation, delays and compliance hurdles.

About the Author

Prashant Kumar is a Company Secretary, Published Author, and Partner at Eclectic Legal, where he advises businesses on corporate governance, regulatory strategy and brand protection. His team regularly assists Indian and global companies with Freedom to Operate (FTO) searches, patent-risk assessments, product commercialisation strategy and international market-entry compliance.

He can be reached for consultations at +91-9821008011 or prashant@eclecticlegal.com

[…] is done, not merely whether it is done. The same logic underpins the distinction explained in FTO vs Patentability Search: What’s the Difference and When Do You Need Each?, a distinction that courts and investors increasingly expect businesses to […]