A practical guide to choosing the right instrument for foreign capital inflow

By Prashant Kumar

Introduction

Every business exploring global investment eventually faces a critical decision: what is the correct legal route to bring foreign money into India? Many assume that “FDI” is the only answer, but India’s regulatory framework under FEMA, the Companies Act, and RBI guidelines provides a wide spectrum of instruments: pure equity, preference shares, convertible debentures, overseas borrowings, or even hybrid structures. Each option affects pricing rules, dilution, interest burden, control rights, reporting obligations, sector caps, and the business’s long-term strategy.

Choosing the wrong route can lead to blocked remittances, AD Bank objections, delays in FC-GPR filings, penalties, or even compounding applications. This guide breaks down every major inflow route used by Indian businesses today — FDI, CCPS, CCDs, and ECB — with practical examples, compliance requirements, and a simple decision lens to select the right structure for your next inflow.

What is the best way for a business to bring foreign money into India?

There is no universal “best” route. Businesses choose between FDI equity, CCPS, CCDs, ECB, or convertible notes depending on valuation clarity, interest servicing capacity, governance expectations, sector caps, and long-term capital requirements. Equity suits stable valuations, CCPS or CCDs help manage uncertainty, and ECB works when debt is better than dilution.

Understanding the Four Primary Capital Inflow Routes

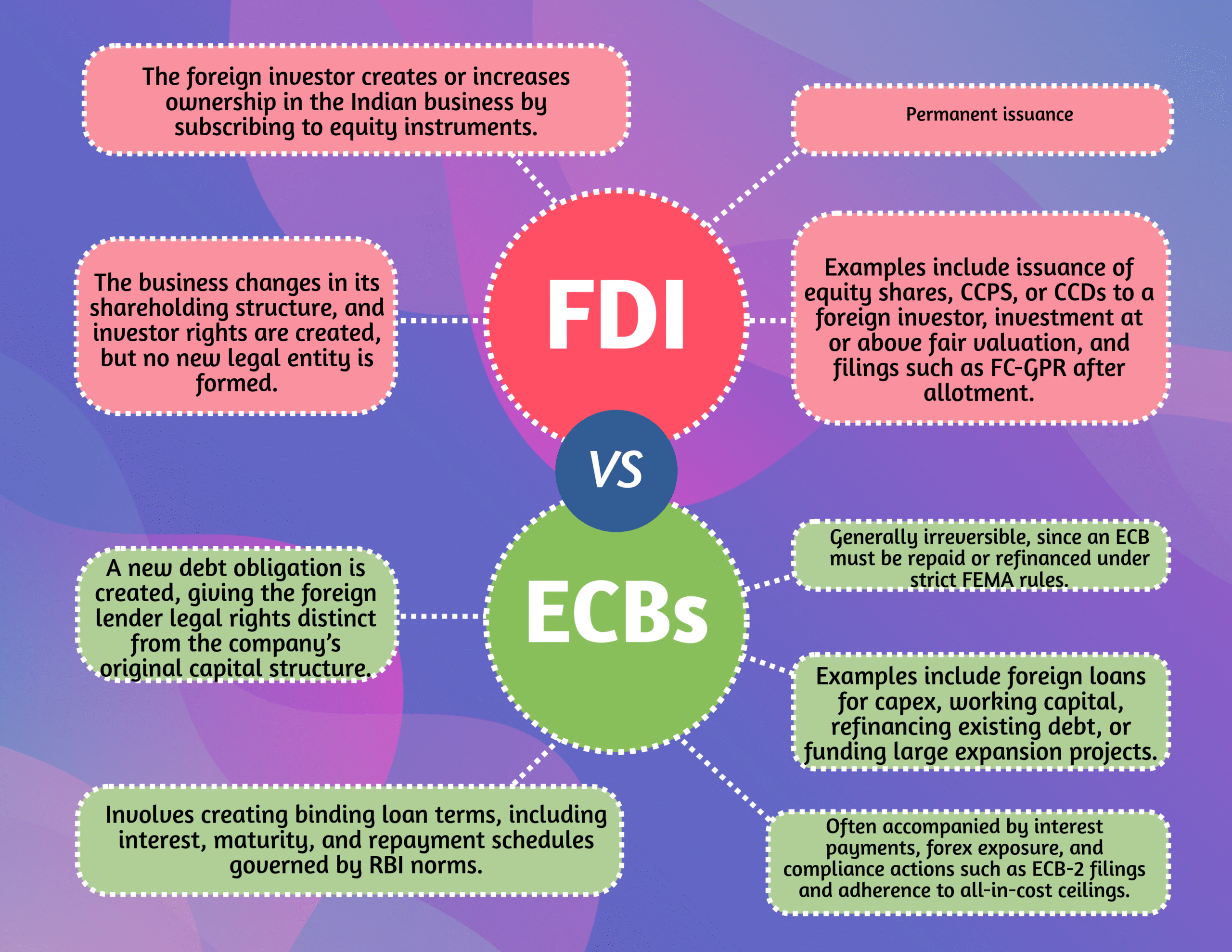

FDI Equity: Clean, Simple, and Ideal When Valuation Is Clear

FDI equity is the most widely used method. A foreign investor directly subscribes to equity shares at or above a fair valuation certified by a CA or merchant banker. This route is governed by the pricing guidelines and sectoral rules under FEMA and the Consolidated FDI Policy. Once funds arrive through SWIFT remittance and the AD Bank issues a Foreign Inward Remittance Certificate, the company must allot shares within 60 days and file its FC-GPR form within the next 30 days.

This route works best when valuations are stable and the investment is strategic. For example, a manufacturing business raising ₹25 crore from a Singapore-based PE fund typically uses FDI equity because voting rights, board seats, and governance structures align with long-term partnership expectations. However, if valuation is uncertain — common in early-stage or rapidly evolving companies — businesses often avoid immediate equity to prevent unnecessary dilution.

CCPS: The Preferred Instrument for Flexible, Rights-Heavy Investments

Compulsorily Convertible Preference Shares are often referred to as the “venture capital instrument” of India because they combine the flexibility of debt-like economics with equity treatment under FEMA. CCPS give investors a preferential dividend, liquidation preference, and structured conversion rights, but they must convert into equity at a pre-agreed formula or valuation. RBI and SEBI both treat CCPS as “equity instruments”, which means they fall under the FDI automatic route in most sectors.

Businesses choose CCPS when investors want priority returns without exerting immediate control. A common example is a technology company raising $2 million from an overseas venture fund in multiple tranches. The fund may expect liquidation preference, anti-dilution rights, and milestone-based conversion — all of which CCPS can accommodate legally. CCPS also help avoid valuation disputes by linking conversion to a future valuation event.

CCDs: Structured Protection for Investors, Equity Treatment Under FEMA

Compulsorily Convertible Debentures begin as debt but must convert to equity within a defined period. Because the conversion is mandatory, RBI treats CCDs as equity instruments under FDI rules. CCDs are particularly effective where valuation is unclear but investors expect predictable, formula-based returns. While CCDs may carry interest, it is usually kept nominal to reduce cash flow pressure on the company.

Consider an infrastructure services company raising funds from an overseas investor where cash flows are predictable but valuation is evolving. A CCD structure lets the investor secure a fixed IRR through conversion pricing while allowing the company to postpone equity dilution until operational performance stabilises. The challenge lies in ensuring the conversion formula complies strictly with FEMA guidelines; ambiguity is a common reason for FC-GPR rejections.

ECB: Ideal for Working Capital, Capex, and Non-Dilutive Expansion

External Commercial Borrowings allow Indian companies to borrow funds from overseas lenders — banks, funds, parent companies, or foreign shareholders. ECB is tightly regulated: RBI prescribes eligible borrowers, all-in-cost ceilings, minimum average maturity periods, permitted end-uses, and monthly reporting requirements.

ECB suits businesses that prefer debt over dilution. For example, a logistics company building regional warehousing facilities may borrow $5 million through ECB at favourable foreign interest rates, using the funds exclusively for capex. However, a young company with unpredictable revenue should avoid ECB because interest and repayments require consistent foreign exchange outflows. ECB also requires an LRN (Loan Registration Number) before drawdown, monthly ECB-2 filings, and strict adherence to end-use and cost norms.

How does FEMA regulate these capital inflow routes?

FEMA regulates foreign capital by enforcing sectoral limits, pricing rules, KYC norms, interest caps, end-use restrictions, and strict reporting through FC-GPR, FC-TRS, ECB filings, and annual returns. Every inflow — equity or debt — must follow precise timelines, documentation requirements, and AD Bank verification.

FEMA’s core objective is clarity and traceability. Whether the inflow is equity or borrowing, FEMA ensures that foreign capital enters through legitimate banking channels with complete documentation. KYC reports from the remitting bank, proper SWIFT remittances, valuation certificates, share allotment resolutions, and form filings create a complete compliance trail. Non-compliance can lead to compounding applications and penalties, especially for late FC-GPR filings — a situation many businesses face when AD Banks reject filings triggered by valuation mismatch, missing KYC, or incorrect instrument classification.

Key Decision Factors: Which Route Should a Business Choose?

A business must assess valuation certainty, cash flow stability, sectoral regulations, investor expectations, and long-term strategy. If valuation is clear and governance alignment already exists, equity is the simplest route. If valuation is uncertain or the investor expects preferences, CCPS or CCDs work better. For companies with stable cash flow and a need for non-dilutive capital, ECB offers significant advantages.

In practice, businesses also consider speed. Convertible instruments often close faster because valuation debates are deferred. Sector regulations also matter; for instance, FDI caps in insurance or retail may push a business to ECB even if the original plan involved equity.

Common Mistakes Businesses Make During Foreign Inflows

Many businesses attempt to issue instruments without proper FEMA-compliant conversion formulas, particularly in CCD structures. Others accept shareholder loans from foreign parents without following ECB regulations, resulting in violations. Some rely on valuation reports provided by investors that do not meet Indian regulatory standards. A recurring issue is missing the 60-day allotment window or the 30-day FC-GPR timeline, which leads to avoidable penalties. Businesses also sometimes seek unnecessary government approvals even when the automatic route is available.

Scenario-Based Guidance

A young technology business should prefer CCPS because it supports multi-tranche investment, milestone-linked conversion, and investor protection without forcing premature valuation. A manufacturing or logistics company expanding its facilities may find ECB more efficient than equity because it preserves ownership. A business facing short-term working capital pressures but expecting long-term growth may choose CCDs that convert after reaching operational milestones. A business with stable valuation and clear governance expectations from the investor should choose FDI equity for simplicity and regulatory cleanliness.

Related Readings

You may also find these posts helpful:

- ESOP Compliance and Taxation in India — What Businesses Should Know

- Private Limited vs LLP in India (2025) – Legal & Tax Comparison

These articles help create continuity between fundraising, governance, and regulatory management.

FAQs

1. Can a foreign investor give a simple loan to an Indian business?

Not unless the loan meets ECB requirements. FEMA does not allow ordinary shareholder loans from foreign investors unless they fall strictly under the ECB framework. This includes compliance with all-in-cost ceilings, permitted end-uses, minimum maturity periods, KYC, LRN, and monthly ECB-2 filings. For example, if a UK parent wants to support its Indian subsidiary with a ₹20 crore working capital loan, it cannot simply wire funds and sign a basic loan agreement. It must register the loan under ECB and follow interest caps and reporting timelines. Any deviation results in an automatic violation and may require compounding.

2. Which is the safest and cleanest FEMA-compliant option for foreign investment?

FDI equity and CCPS are the safest and most widely accepted. They fall under the automatic route in most sectors, carry minimal regulatory scrutiny, and offer complete flexibility for repatriation on exit. A business raising money for long-term growth — especially from institutional investors — is usually better off with FDI equity or CCPS because AD Banks process these transactions quickly and FEMA compliance is straightforward.

3. Can CCPS or CCDs have open-ended or variable conversion pricing?

They can follow a formula, but the formula must be FEMA-compliant. FEMA does not permit optionality in conversion or unclear pricing structures that resemble disguised debt or future valuation manipulation. For instance, a conversion formula based on “next round valuation minus a discount” is acceptable, but a formula that leaves conversion price completely open is not. AD Banks often reject FC-GPR filings where conversion formulas lack specificity, which forces businesses into compounding applications.

4. Do all foreign inflow instruments require valuation?

Equity, CCPS, and CCDs require valuation at or above a fair value determined by a SEBI-registered merchant banker or a Chartered Accountant using internationally accepted pricing methodologies. ECB does not require valuation, but it has strict rules on interest caps based on benchmark rates and mandatory reporting. If an investor remits $1 million into a CCPS structure, the business must file a valuation certificate before allotment, but if the same investor gives the company an ECB loan, valuation is irrelevant — interest caps and end-use restrictions take precedence.

5. Can a business raise FDI and ECB at the same time?

Yes. Many businesses use a combination of equity and overseas borrowing. For example, a solar manufacturing company may raise equity through CCPS from a US investor while simultaneously drawing ECB from a European bank for capex financing. Both routes must independently comply with FEMA reporting, but coexistence is permitted. Businesses must ensure each inflow is tracked separately, especially in annual filings like FLA and ECB-2.

Closing Note

When businesses align their capital inflow structure with valuation maturity, sector rules, governance expectations, and cash flow realities, foreign investment becomes much smoother and legally safer. India’s FEMA framework is detailed and sometimes unforgiving, but it also offers tremendous flexibility. Choosing the right instrument — equity, CCPS, CCDs, or ECB — ensures your global investment strengthens long-term growth rather than becoming a regulatory burden.

About the Author

Prashant Kumar is a Company Secretary, Published Author, and Partner at Pratham Legal, a full-service Indian law firm advising on corporate, regulatory, and transactional matters. He specialises in corporate governance, legal compliance, and brand protection, helping businesses build credible and sustainable legal foundations. He can be reached for discussions on brand strategy, compliance, and governance excellence via LinkedIn.